The late 60’s were not a time of artistic triumph. Theatrical animation was on the wane, and the few studios left offering such product struggled both to keep relevant and to keep within small budgets. Unable in many instances to maintain established characters due either to prohibitive contractual commitments or inability to render them suitably in limited animation, new characters would be given the push in hopes that something would click. Sometimes this would work, despite animation quality more suited to TV, as in the case of newly-established DePatie-Freleng. Others, like Paramount, would never achieve results resembling their former successes. As distributors found less and less use for the theatrical short, depending on the feature alone to maintain box office, the need for the medium dried up, with the short becoming Saturday morning TV fare.

Despite all these changes, robots remained a popular subject for animation, still thought to be on the cutting edge of modern technology (which was already beginning in real life to become accustomed to the calculating abilities of the super-computer). Also, great interest centered during this era upon the exploits of NASA and the Soviets in the space race, such that it was only a matter of logical progression that the concept of the robot would travel with man into the heavens, becoming more associated with interstellar adventure rather than merely conducting domestic chores. These concepts further merged near the very end of this week’s survey into a theatrical craze from a highly successful live-action franchise launched by LucasFilms, which still remains a heavyweight to this day, updating 30’s style serial adventure into the far far away future of the stars. Animation was quick to parody this success, frequently in TV but even in a last gasp of theatrical action, which will close out coverage for this installment. There would be further robot action on the big screen in later productions, but as part of feature presentations rather than shorts, to be discussed in later articles along this trail.

I begin this week’s coverage with an oversight that properly belonged in a past installment. It was a bit easy to overlook, as there is no creature of tin or steel. Instead, it is part of the imaginings of Donald Duck, in “Donald’s Diary” (Disney/RKO, 2/13/54 – Jack Kinney, dir.). Kinney was prone to taking things in odd directions when he would dabble in series usually reserved for another director. He takes his own liberties freely with this one, chronicling a budding romance between Donald and Daisy (who, in the set-up for this story, have never met before). Things are different even from the opening theme music, reorchestrating the Donald theme, then segueing into an original melody that underscores most of the film. Set in San Francisco (with impressionistic backgrounds portraying most scenes on severe hilly slopes), Kinney makes some cast changes and personality changes to put across his original storyline. Daisy, with peach-colored feathers and voiced for the only time in the series by June Foray (her lines would be replaced in favor of a more traditional Daisy voice in wraparound animation for the TV compilation, “This Is Your Life, Donald Duck”), is a devious man-catcher rather than merely waiting to be courted, setting various schemes into motion to attract Donald’s attention, and finally getting her prey to stop and take notice by setting a hunter’s snare trap. Donald eventually takes the bait, and buys a ring, seeking to pop the question. Daisy’s mother and father (seen for the only time in the series’ history) lie in wait with camera and recording equipment to retain evidence of the proposal in case of a breach of promise suit. (Notably, in a cameo, even Huey, Louie, and Dewey are recast as Daisy’s brothers, rather than Donald’s nephews.) As Daisy keeps Donald waiting in the living room while she overdoes it on finishing a shower, Donald drifts off to sleep, and imagines his marriage, honeymoon – and the nightmare after the honeymoon.

I begin this week’s coverage with an oversight that properly belonged in a past installment. It was a bit easy to overlook, as there is no creature of tin or steel. Instead, it is part of the imaginings of Donald Duck, in “Donald’s Diary” (Disney/RKO, 2/13/54 – Jack Kinney, dir.). Kinney was prone to taking things in odd directions when he would dabble in series usually reserved for another director. He takes his own liberties freely with this one, chronicling a budding romance between Donald and Daisy (who, in the set-up for this story, have never met before). Things are different even from the opening theme music, reorchestrating the Donald theme, then segueing into an original melody that underscores most of the film. Set in San Francisco (with impressionistic backgrounds portraying most scenes on severe hilly slopes), Kinney makes some cast changes and personality changes to put across his original storyline. Daisy, with peach-colored feathers and voiced for the only time in the series by June Foray (her lines would be replaced in favor of a more traditional Daisy voice in wraparound animation for the TV compilation, “This Is Your Life, Donald Duck”), is a devious man-catcher rather than merely waiting to be courted, setting various schemes into motion to attract Donald’s attention, and finally getting her prey to stop and take notice by setting a hunter’s snare trap. Donald eventually takes the bait, and buys a ring, seeking to pop the question. Daisy’s mother and father (seen for the only time in the series’ history) lie in wait with camera and recording equipment to retain evidence of the proposal in case of a breach of promise suit. (Notably, in a cameo, even Huey, Louie, and Dewey are recast as Daisy’s brothers, rather than Donald’s nephews.) As Daisy keeps Donald waiting in the living room while she overdoes it on finishing a shower, Donald drifts off to sleep, and imagines his marriage, honeymoon – and the nightmare after the honeymoon.

Much like “Porky’s Romance” at Warner Brothers, Donald loses quickly his role as head of household, as Daisy occupies the easy chair, takes all his money the minute he comes home on a payday, feeds him char-burnt food, and delegates him trash duty, dishwashing while locked in a set of stocks, and other demeaning tasks. Donald (in narrative read from the pages of his diary, provided by the same voice who recurrently gave Donald or his doubles Ronald Colman speech abilities in episodes of the 1940’s) writes “I was losing my identity. I had become – a robot!” Suddenly, as Donald’s eyes rotate in weird manner independent of one another, a large key such as that of a mechanical toy sprouts from his back. Donald’s eyes glaze over, rigid and bolted in a forward gaze, as he assumes a walk suggesting his legs have become a set of rotating rolling wheels. Without emotion or expression, he mechanically and methodically mows lawns, dusts furniture, beats rows of carpets, puts out the cat, and washes tons of more dishes, all portrayed in rapid-fire cuts and multiple exposures that harken to the nightmare finale of the studio’s previous success in Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943). As multiple images of Donald coalesce in the center of the screen, they explode, dissolving the shot back to Donald sleeping in Daisy’s living room chair. Daisy is finally ready, coaxing “Dreamer Boy” to wake up. Donald takes one look, screams his loudest “WAAKK!”, and exits without opening the door, leaving a silhouette-shaped hole. His last diary entry is made from a location suitable for a bachelor escaping a bad romance – at a remote outpost manning the fort walls in the Foreign Legion.

Much like “Porky’s Romance” at Warner Brothers, Donald loses quickly his role as head of household, as Daisy occupies the easy chair, takes all his money the minute he comes home on a payday, feeds him char-burnt food, and delegates him trash duty, dishwashing while locked in a set of stocks, and other demeaning tasks. Donald (in narrative read from the pages of his diary, provided by the same voice who recurrently gave Donald or his doubles Ronald Colman speech abilities in episodes of the 1940’s) writes “I was losing my identity. I had become – a robot!” Suddenly, as Donald’s eyes rotate in weird manner independent of one another, a large key such as that of a mechanical toy sprouts from his back. Donald’s eyes glaze over, rigid and bolted in a forward gaze, as he assumes a walk suggesting his legs have become a set of rotating rolling wheels. Without emotion or expression, he mechanically and methodically mows lawns, dusts furniture, beats rows of carpets, puts out the cat, and washes tons of more dishes, all portrayed in rapid-fire cuts and multiple exposures that harken to the nightmare finale of the studio’s previous success in Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943). As multiple images of Donald coalesce in the center of the screen, they explode, dissolving the shot back to Donald sleeping in Daisy’s living room chair. Daisy is finally ready, coaxing “Dreamer Boy” to wake up. Donald takes one look, screams his loudest “WAAKK!”, and exits without opening the door, leaving a silhouette-shaped hole. His last diary entry is made from a location suitable for a bachelor escaping a bad romance – at a remote outpost manning the fort walls in the Foreign Legion.

“Robot Rival” (Paramount, Modern Madcap (Zippy Zephyr), 8/64 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – From the presentation of this cartoon, with a somewhat catchy original theme song by Win Sharples, and a “Featuring” full-screen still of the starring character in the credits (a rarity for Modern Madcaps), it looks like someone thought this character had potential to launch a series. But, as Top Cat often said when a bad joke fell flat, “Nothin’”. Out “hero” is a rocket-jockey taxt driver of the future, working for the Interplanet Taxi Company, a service that handles calls anywhere in the galaxy. (Fare regulation still seems to be in effect in the future, as the side of Zippy’s rocket cab states a set rate of 25 cents for first 10,000 miles.) Zippy is apparently the misfit of the company’s drivers, and his overbearing boss would like nothing better than to get rid of him. Voices for the film are uncredited and speculative, seemingly mis-attributed by IMDB, who erroneously gives Zippy’s credit to Eddie Lawrence, although the voice is far lighter than Lawrence’s Swifty. IMDB also speculates the Boss’s voice to be Dayton Allen (perhaps possible). I believe it more likely all male voices are supplied by Bob McFadden (as the track sounds a lot like the mix of voices in a Sadcat cartoon), or that Zippy’s voice is perhaps supplied by Lionel Wilson.

“Robot Rival” (Paramount, Modern Madcap (Zippy Zephyr), 8/64 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – From the presentation of this cartoon, with a somewhat catchy original theme song by Win Sharples, and a “Featuring” full-screen still of the starring character in the credits (a rarity for Modern Madcaps), it looks like someone thought this character had potential to launch a series. But, as Top Cat often said when a bad joke fell flat, “Nothin’”. Out “hero” is a rocket-jockey taxt driver of the future, working for the Interplanet Taxi Company, a service that handles calls anywhere in the galaxy. (Fare regulation still seems to be in effect in the future, as the side of Zippy’s rocket cab states a set rate of 25 cents for first 10,000 miles.) Zippy is apparently the misfit of the company’s drivers, and his overbearing boss would like nothing better than to get rid of him. Voices for the film are uncredited and speculative, seemingly mis-attributed by IMDB, who erroneously gives Zippy’s credit to Eddie Lawrence, although the voice is far lighter than Lawrence’s Swifty. IMDB also speculates the Boss’s voice to be Dayton Allen (perhaps possible). I believe it more likely all male voices are supplied by Bob McFadden (as the track sounds a lot like the mix of voices in a Sadcat cartoon), or that Zippy’s voice is perhaps supplied by Lionel Wilson.

Circulating print as aired by Nickelodeon contains an odd break in the transfer toward the beginning of the film (though a second broadcast included the missing footage), as Zippy brings his cab into headquarters in a collision with a rocket car in the parking lit – the boss’s car, the remains of which are now spread over five parking spaces. The boss has had it, and calls the company mechanic (Luna Tic) to wheel in a robot roughly resembling the tin man of Oz, whom he intends to use as Zippy’s replacement. A unique feature of the robot is a lever on his head matching the flag used to activate taxi meters, which when pulled opens the robot’s eyes. The boss states the savings on installing taxi meters alone justifies substituting the robots into service. Zippy begs for another chance, asking the boss to think of his girl friend, and showing him a picture of her and Zippy together. (The girl looks like Bunny, recently animated by Kneitel in the King Features Beetle Bailey cartoons.) “Don’t let romance fade out of my life”, saus Zippy, while the photo image of his girl fades slowly out of the picture. The boss relents, as a call comes in to pick up a passenger on Saturn. He offers a challenge – the first driver to return with that passenger gets the job. “Fair?”, asks the boss. “Fare” responds the robot, by flashing what is printed on his meter flag.

Circulating print as aired by Nickelodeon contains an odd break in the transfer toward the beginning of the film (though a second broadcast included the missing footage), as Zippy brings his cab into headquarters in a collision with a rocket car in the parking lit – the boss’s car, the remains of which are now spread over five parking spaces. The boss has had it, and calls the company mechanic (Luna Tic) to wheel in a robot roughly resembling the tin man of Oz, whom he intends to use as Zippy’s replacement. A unique feature of the robot is a lever on his head matching the flag used to activate taxi meters, which when pulled opens the robot’s eyes. The boss states the savings on installing taxi meters alone justifies substituting the robots into service. Zippy begs for another chance, asking the boss to think of his girl friend, and showing him a picture of her and Zippy together. (The girl looks like Bunny, recently animated by Kneitel in the King Features Beetle Bailey cartoons.) “Don’t let romance fade out of my life”, saus Zippy, while the photo image of his girl fades slowly out of the picture. The boss relents, as a call comes in to pick up a passenger on Saturn. He offers a challenge – the first driver to return with that passenger gets the job. “Fair?”, asks the boss. “Fare” responds the robot, by flashing what is printed on his meter flag.

Zippy’s cab and a second piloted by the robot blast off side by side. Zippy almost misses the boat when he leans out to get a good-luck kiss from his girl, but the rocket drags him away, almost throwing him from the cockpit. Zippy regains the steering wheel, and concentrates on catching up with the robot, who has taken the lead. As Zippy approaches, the robot’s cab extends a large magnet out its rear, attracting and catching Zippy’s cab with it. Zippy thinks he’s figured the robot all wrong, as it appears that he is giving Zippy a lift. Instead, the magnet turns Zippy’s cab to face in the opposite direction, then a robotic hand inserts a large skyrocket into the exhaust of Zippy’s jets and lights the fise. Zippy is blasted backwards in the opposite direction. He recovers, and uses the skyrocket’s power to catch back up to the robot cab. Two can play rough, Zippy proclaims, as he pulls ahead of the robot, and inserts a chewed piece of chewing gum into the exhaust system of his own jets.

The engine inflates the gum into a huge bubble behind Zippy’s engine, then releases it all over the robot’s cab. The robot retaliates with another robotic arm extension equipped with a giant shaving razor, and shaves away the gum, tossing it forward onto Zippy’s cab. As Zippy wonders who turned out the lights, his cab runs into a stray flock of birds (in outer space????), resulting in his cab being “gummed and feathered”. Zippy pills a lever activating a retro rocket, and quickly brakes to a standstill, allowing the gum to detach itself from the cab with its forward momentum. The gum flies ahead, again falling upon the robot cab, as Zippy soars into the lead. We oddly do not hear or see from the robot cab for te remainder of the cartoon, with no explanation why it does not use the razor again, or stay in competition with Zippy for the Saturn passenger. Also denoting an unexplained writer’s block, though Zippy seems to remember correctly the street corner at which he is to pick up his passenger, he inexplicably picks up a passenger at the wrong intersection. (Shouldn’t he, the experienced driver, know Saturn’s thoroughfares like the back of his hand?) The passenger is taken aback as Zippy rolls out the “red carpet treatment”, with a mechanical device to roll the passenger up in a red rug and haul him aboard the rocket. It turns out the passenger was a wanted criminal waiting for members of his gang to pick him up, and though he threatens suit and demands a $1,000 settlement when delivered wrongfully to the taxi company headquarters, he is quickly recognized by a passing space cop, and Zippy receives the $1,000 as a reward. Zippy faints, which Luna Tic attributes to the shock of “meeting Benjamin Franklin face to face.” Luna has somehow regained the robot driver from nowhere (how did the robot get back, when it couldn’t even find the Saturn passenger, who is still waiting on the planet?), and Luna wishes that something like Zippy’s good fortune would happen to him, just once. He ponds on the robot’s back, which loosens the meter flag on the robot’s head like the arm of a slot machine. Wheels spin in the robot’s eyes, and come up with the words, Jack Pot. The robot pays off, spilling a flood of coins out of its mouth, as Luna rejoices, “I did it! I did it!”

The engine inflates the gum into a huge bubble behind Zippy’s engine, then releases it all over the robot’s cab. The robot retaliates with another robotic arm extension equipped with a giant shaving razor, and shaves away the gum, tossing it forward onto Zippy’s cab. As Zippy wonders who turned out the lights, his cab runs into a stray flock of birds (in outer space????), resulting in his cab being “gummed and feathered”. Zippy pills a lever activating a retro rocket, and quickly brakes to a standstill, allowing the gum to detach itself from the cab with its forward momentum. The gum flies ahead, again falling upon the robot cab, as Zippy soars into the lead. We oddly do not hear or see from the robot cab for te remainder of the cartoon, with no explanation why it does not use the razor again, or stay in competition with Zippy for the Saturn passenger. Also denoting an unexplained writer’s block, though Zippy seems to remember correctly the street corner at which he is to pick up his passenger, he inexplicably picks up a passenger at the wrong intersection. (Shouldn’t he, the experienced driver, know Saturn’s thoroughfares like the back of his hand?) The passenger is taken aback as Zippy rolls out the “red carpet treatment”, with a mechanical device to roll the passenger up in a red rug and haul him aboard the rocket. It turns out the passenger was a wanted criminal waiting for members of his gang to pick him up, and though he threatens suit and demands a $1,000 settlement when delivered wrongfully to the taxi company headquarters, he is quickly recognized by a passing space cop, and Zippy receives the $1,000 as a reward. Zippy faints, which Luna Tic attributes to the shock of “meeting Benjamin Franklin face to face.” Luna has somehow regained the robot driver from nowhere (how did the robot get back, when it couldn’t even find the Saturn passenger, who is still waiting on the planet?), and Luna wishes that something like Zippy’s good fortune would happen to him, just once. He ponds on the robot’s back, which loosens the meter flag on the robot’s head like the arm of a slot machine. Wheels spin in the robot’s eyes, and come up with the words, Jack Pot. The robot pays off, spilling a flood of coins out of its mouth, as Luna rejoices, “I did it! I did it!”

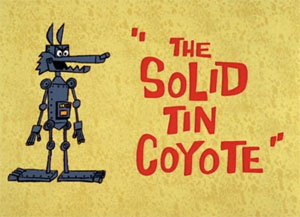

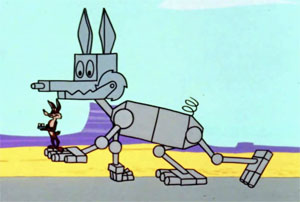

“The Solid Tin Coyote” (Warner, Road Runner, 2/19/66 – Rudy Larriva, dir.) – Impressive for a memorable design, but typically falling far short on pacing, director Larriva brings Wile E. Coyote into full robotic mode in mammoth proportions. (The film’s title is a play on that of a recent feature film, “The Solid Gold Cadillac”.) A stray fall into a canyon junkyard suddenly gives Wile E. a brainstorm to create a new invention. Erecting multistory scaffolding, the coyote constructs a robot eight stories tall, in his own image. He devises a radio remote-control box, with the monster picking up the signals in electrical beams which flash between the contraption’s huge erect ears. The curious Road Runner is on hand for the creation’s unveiling, and for once is startled, hitting the road in a hurry. Wile E. tests out his baby with a simple initial command on the control box: “Walk”. The robot obeys, taking one clanking footstep forward after another. Soon, Wile E. realizes it is coming too close in his own direction, and sends signals from the control to “Stop” and “Halt”. Too late, as a huge metallic foot flattens the coyote, following which he pops ip, pleated like the bellows of an accordion.

“The Solid Tin Coyote” (Warner, Road Runner, 2/19/66 – Rudy Larriva, dir.) – Impressive for a memorable design, but typically falling far short on pacing, director Larriva brings Wile E. Coyote into full robotic mode in mammoth proportions. (The film’s title is a play on that of a recent feature film, “The Solid Gold Cadillac”.) A stray fall into a canyon junkyard suddenly gives Wile E. a brainstorm to create a new invention. Erecting multistory scaffolding, the coyote constructs a robot eight stories tall, in his own image. He devises a radio remote-control box, with the monster picking up the signals in electrical beams which flash between the contraption’s huge erect ears. The curious Road Runner is on hand for the creation’s unveiling, and for once is startled, hitting the road in a hurry. Wile E. tests out his baby with a simple initial command on the control box: “Walk”. The robot obeys, taking one clanking footstep forward after another. Soon, Wile E. realizes it is coming too close in his own direction, and sends signals from the control to “Stop” and “Halt”. Too late, as a huge metallic foot flattens the coyote, following which he pops ip, pleated like the bellows of an accordion.

Wile E. takes up a presumably safer position of command, instructing the robot via a new command box to lower and raise its hand, picking up Wile E. on the level tin platform of the robot’s paw so that he can ride along during the pursuit. As the Road Runner passes, Wile E. gives the command to “Hunt”. The sound of a somewhat off-key hunting horn is heard, as the robot bends slightly forward into the wind, and soon is stomping along the highway, keeping an even pace with the Road Runner. Wile E. issues a new command – “Strike”. He should have indicated with which hand, as the robot turns its left palm in the direction of the ground – which just happens to be the hand on which Wile E. is standing – and strikes repeated blows at the Road Runner, who briskly dodges each impact. Not so the coyote, who again is flattened like a pancake against the palm of the robot’s hand.

Wile E. takes up a presumably safer position of command, instructing the robot via a new command box to lower and raise its hand, picking up Wile E. on the level tin platform of the robot’s paw so that he can ride along during the pursuit. As the Road Runner passes, Wile E. gives the command to “Hunt”. The sound of a somewhat off-key hunting horn is heard, as the robot bends slightly forward into the wind, and soon is stomping along the highway, keeping an even pace with the Road Runner. Wile E. issues a new command – “Strike”. He should have indicated with which hand, as the robot turns its left palm in the direction of the ground – which just happens to be the hand on which Wile E. is standing – and strikes repeated blows at the Road Runner, who briskly dodges each impact. Not so the coyote, who again is flattened like a pancake against the palm of the robot’s hand.

So how about an even safer command position – atop the robot’s head? Sounds reasonable, except for those electrical beams by which the robot picks up its radio commands. Wile E. gets caught in the cross-fire of electrical current, and is turned multiple shades of neon glow before he emerges from between the ears well-fried.

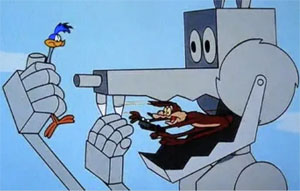

Wile E. returns to position upon the robot’s hand as the best of his prior options, and installs two conical fang teeth into the robot’s upper jaw. He then repeats the “Hunt” command, setting the robot into motion. To everyone’s surprise, the monster actually catches the Road Runner in one hand, raising him up close to the robot’s jaws. In an odd choice of commands, as we would assume Wile E. would want the bird to satisfy his own hunger, Wile E. issues instructions on the control box – “Eat, Stupid”. The robot has odd tastes, choosing as his meal Wile E, instead of the bird (perhaps taking things literally – after all, which of the two is more stupid?). Wile E. utters some painful-sounding screams and yips as the robot’s jaws masticate, then emerges somewhat the worse for wear out of the robot’s ear. With no regard for the previous problem of the electrical signals between the ears, and with no explanation of why the robot seems to have let the Road Runner go, Wile E. gives another control-box order: “One more time, you idiot!” (Who’s writing his dialogue – Ren Hoek?) The robot charges down the road again. But this time, the Road Runner is waiting for him – on the opposite side of a wide canton, with the road about to end on the robot’s side. Wile E. uses every variant on his control box to issue the same command: “Turn”, “Stop”, “Halt”, “Back, “Whoa”, “Reverse”, and “Heel” – but of course it’s no use. The robot and Wile E. Fall once again into the canyon, where the robot winds up a heap of its component junk parts, while the sounds of the off-key hunting horn and the Road Runner’s mocking “Beep Beep”s is heard on the track to rub it in to Wile E., for the fade out.

Wile E. returns to position upon the robot’s hand as the best of his prior options, and installs two conical fang teeth into the robot’s upper jaw. He then repeats the “Hunt” command, setting the robot into motion. To everyone’s surprise, the monster actually catches the Road Runner in one hand, raising him up close to the robot’s jaws. In an odd choice of commands, as we would assume Wile E. would want the bird to satisfy his own hunger, Wile E. issues instructions on the control box – “Eat, Stupid”. The robot has odd tastes, choosing as his meal Wile E, instead of the bird (perhaps taking things literally – after all, which of the two is more stupid?). Wile E. utters some painful-sounding screams and yips as the robot’s jaws masticate, then emerges somewhat the worse for wear out of the robot’s ear. With no regard for the previous problem of the electrical signals between the ears, and with no explanation of why the robot seems to have let the Road Runner go, Wile E. gives another control-box order: “One more time, you idiot!” (Who’s writing his dialogue – Ren Hoek?) The robot charges down the road again. But this time, the Road Runner is waiting for him – on the opposite side of a wide canton, with the road about to end on the robot’s side. Wile E. uses every variant on his control box to issue the same command: “Turn”, “Stop”, “Halt”, “Back, “Whoa”, “Reverse”, and “Heel” – but of course it’s no use. The robot and Wile E. Fall once again into the canyon, where the robot winds up a heap of its component junk parts, while the sounds of the off-key hunting horn and the Road Runner’s mocking “Beep Beep”s is heard on the track to rub it in to Wile E., for the fade out.

Watch it over HERE.

The writers for Chuck Jones apparently wanted to keep Tom and Jerry relevant to modern audiences, by adapting them to the fads, trends, and genres of the day – sometimes at the expense of their underlying personalities. This is evident from four late installments in their last theatrical series. The first not only kept things current, but served as an effective meas of plugging the product of Chuck’s financing bosses at MGM – who at the time were involved in a successful television franchise capitalizing on the trend for secret agent shows in the wake of the James Bond craze – a series for NBC called “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.” It didn’t hurt the show’s efforts to cash in on the Bond bonanza that Ian Fleming himself was a contributor to the show’s development. The series would prove popular enough that it woild spawn a spinoff, “The Girl From U.N.C.L.E.” So why not, “The Mouse From H.U.N.G.E.R.”? (4/21/67 – Abe Levitow, dir.) Jerry portrays the secret agent, keeping his demeanor as cool as possible throughout (despite a moment of embarrassment, when he checks on his arsenal of concealed weapons inside his trenchcoat, then accidentally sets them off upon himself when he tightens his belt). He plays on the standard trope of a secret entrance to end all secret entrances in getting into headquarters – including giving a tobacco store wooden Indian a hotfoot with a revolver that is really a cigarette lighter, then entering a secret mousehole behind the Indian’s raised foot, to climb to the cigars in the Indian’s hand, and ride inside one as a miniature rocket into headquarters. Receiving orders, he rides to the scene of cheese in a souped-up spy dragster. And he faces the villainous Tom Thrush at his foreboding lair (”Thrush” being the name of the opposing secret organization from the television series). Tom attempts to defend his giant refrigerator full of cheese by various levels of booby traps. First, he presses a button to slam a steel door across the entrance to the compound, and raise additional layers of barricades, barbed wire, and other obstacles across the entrance road.

The writers for Chuck Jones apparently wanted to keep Tom and Jerry relevant to modern audiences, by adapting them to the fads, trends, and genres of the day – sometimes at the expense of their underlying personalities. This is evident from four late installments in their last theatrical series. The first not only kept things current, but served as an effective meas of plugging the product of Chuck’s financing bosses at MGM – who at the time were involved in a successful television franchise capitalizing on the trend for secret agent shows in the wake of the James Bond craze – a series for NBC called “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.” It didn’t hurt the show’s efforts to cash in on the Bond bonanza that Ian Fleming himself was a contributor to the show’s development. The series would prove popular enough that it woild spawn a spinoff, “The Girl From U.N.C.L.E.” So why not, “The Mouse From H.U.N.G.E.R.”? (4/21/67 – Abe Levitow, dir.) Jerry portrays the secret agent, keeping his demeanor as cool as possible throughout (despite a moment of embarrassment, when he checks on his arsenal of concealed weapons inside his trenchcoat, then accidentally sets them off upon himself when he tightens his belt). He plays on the standard trope of a secret entrance to end all secret entrances in getting into headquarters – including giving a tobacco store wooden Indian a hotfoot with a revolver that is really a cigarette lighter, then entering a secret mousehole behind the Indian’s raised foot, to climb to the cigars in the Indian’s hand, and ride inside one as a miniature rocket into headquarters. Receiving orders, he rides to the scene of cheese in a souped-up spy dragster. And he faces the villainous Tom Thrush at his foreboding lair (”Thrush” being the name of the opposing secret organization from the television series). Tom attempts to defend his giant refrigerator full of cheese by various levels of booby traps. First, he presses a button to slam a steel door across the entrance to the compound, and raise additional layers of barricades, barbed wire, and other obstacles across the entrance road.

These prove of little use, as an insistent honk from Jerry’s auto horn instantly gets everything to open right up and clear the way. Tom next releases what amounts to a modern-day version of the decoy time bomb first used on Woody Woodpecker in “Knock Knock” (1940), in the form of a robot female mouse strutting her stuff in the middle of the road. Jerry screeches to a stop and hops out of his car, anxious to steal a kiss. As his lips touch the robot, an x-ray view of its interior machinery shows that the robot’s lips are connected by a thermometer-style tube to the bomb-activation mechanism, with the increase in temperature from Jerry’s ardor the trigger to set off the explosion. The robot explodes, and Jerry takes the full force of it right in his face. But, as we all know, secret agents are tough – and Jerry, though blackened, merely reacts with an exhale of smoke, which spells in the air the word “WOW”. Tom finally sets the ultimate layering of booby traps, completely lining the interior room leading to the refrigerator as a miniature no-man’s land, with mines, machine guns, barbed wire, and cannons. He lies in wait for the fun in an adjoining room as Jerry enters. Yet all Tom can hear is the unstopping sound of footsteps traversing the room, as if nothing at all were there to interfere. Tom can’t believe his ears, and lets his mind play tricks on him, driving himself to the frenzied thought that he must step in immediately to save his precious cheese. He bursts out of his hiding room – only to find all the booby traps still in place, and ready to blast and explode Tom at every move and footfall. As for those persistent footsteps? They were Jerry’s own trick – played on a tape recorder concealed in an attache case. Tom is decimated and deflated by the time he reaches the other end of the room, not a booby trap untriggered, leaving Jerry a clear field to cart off the refrigerator and all its contents. All Tom has the remaining strength to do is to collapse on the tape recorder’s buttons, causing the tape to play a bugle salute of Taps, and Tom to hold a lily to his chest as he expires. Cue the secret agent music, as Jerry speeds off in his laden spy car down the road.

These prove of little use, as an insistent honk from Jerry’s auto horn instantly gets everything to open right up and clear the way. Tom next releases what amounts to a modern-day version of the decoy time bomb first used on Woody Woodpecker in “Knock Knock” (1940), in the form of a robot female mouse strutting her stuff in the middle of the road. Jerry screeches to a stop and hops out of his car, anxious to steal a kiss. As his lips touch the robot, an x-ray view of its interior machinery shows that the robot’s lips are connected by a thermometer-style tube to the bomb-activation mechanism, with the increase in temperature from Jerry’s ardor the trigger to set off the explosion. The robot explodes, and Jerry takes the full force of it right in his face. But, as we all know, secret agents are tough – and Jerry, though blackened, merely reacts with an exhale of smoke, which spells in the air the word “WOW”. Tom finally sets the ultimate layering of booby traps, completely lining the interior room leading to the refrigerator as a miniature no-man’s land, with mines, machine guns, barbed wire, and cannons. He lies in wait for the fun in an adjoining room as Jerry enters. Yet all Tom can hear is the unstopping sound of footsteps traversing the room, as if nothing at all were there to interfere. Tom can’t believe his ears, and lets his mind play tricks on him, driving himself to the frenzied thought that he must step in immediately to save his precious cheese. He bursts out of his hiding room – only to find all the booby traps still in place, and ready to blast and explode Tom at every move and footfall. As for those persistent footsteps? They were Jerry’s own trick – played on a tape recorder concealed in an attache case. Tom is decimated and deflated by the time he reaches the other end of the room, not a booby trap untriggered, leaving Jerry a clear field to cart off the refrigerator and all its contents. All Tom has the remaining strength to do is to collapse on the tape recorder’s buttons, causing the tape to play a bugle salute of Taps, and Tom to hold a lily to his chest as he expires. Cue the secret agent music, as Jerry speeds off in his laden spy car down the road.

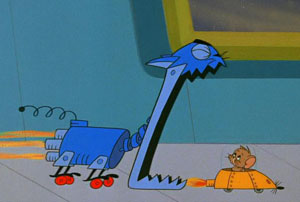

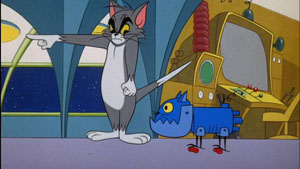

“O Solar Meow” (2/24/67 – Abe Levitow, dir.) brings the duo into another current genre – the fascination with the space race, as well as the current popularity of serious sci-fi brought about by another NBC success, “Star Trek”. An odd trilogy of outer space episodes in future tense would emerge from the studio’s pens, sometimes difficult to distinguish from one another due to their structural similarity, slim plots, identical backgrounds, and reused animation between one episode and another (the other two films being “Guided Mouse-ille, or Science On a Wet Afternoon” (pun on “Seance on a Wet Afternoon”) (3/10/67 – Abe Levitow, dir.), and “Advance and Be Mechanized” (8/25/67 – Ben Washam, dir.) All have Tom and Jerry dwelling aboard an outer-space craft or station (the first episode depicting the craft as manned by actual astronauts, the second showing no supporting crew, and the third a robotic craft designed to mine a moon or asteroid apparently made entirely of cheese). All feature Tom as head of security, and Jerry inside the metal walls of the spacecraft, each at their own version of the TV monitor control panel utilized by Sylvester in “Nuts and Volts”, in control of their own respective robots. Tom’s robot is identical throughout the three episodes – a predominantly-blue quadrupedal device with roller wheels and rocket propulsion. Jerry’s is a yellow mouse-shaped critter on sliding skis instead of feet, also with jet propulsion. Jerry’s model varies after the first episode, the original design allowing for him to ride inside with a passenger seat, while the later model has no rider, and operates solely as a minion to do Jerry’s dirty work.

The first of the three is more creative and original than what follows, and still allows the boys to cause some of their own mischief rather than leaving it all to the robots. It begins with an original idea – launching a ball-shaped supply satellite into space via a giant pinball-machine spring handle. The ball lands in space upon a space station shaped like a tipped roulette wheel, landing in a numbered loading dock on its surface to deposit its cargo – including fresh cheese, desired by Jerry. Jerry hops into his robot, while Tom (alerted by a rocket lit by a fuse ignited as the mouse-robot blasts through a doorway where the line is strung across) sends out the mechanical cat. As the cat closes in with jaws wide to swallow the mouse robot, Jerry shoots a blast of black smoke from the mouse-robot’s jets, leaving the cat-robot coughing and gasping for breath. (Do robots breathe?) The chase leads by Tom’s rolling recliner chair at the command console. The mouse robot scoots under Tom’s chair, while the cat-robot picks up the chair and Tom with him. Tom reaches for a remote and pushes a button to make the robot stop. However, his chair continues to roll – right into the wall. Tom returns to his robot, turns him around, and delivers a swift kick to the robot’s rear. Of course, kicking something of hard metal isn’t too conducive to good pedal health – and Tom’s toes find this out quickly enough, turning red and swelling like balloons, to the cat’s consternation. The remainder of the film does not deal with the robots, but ultimately has Tom fire Jerry off from the station via a space cannon, landing Jerry on the moon. Tom is so happy, he celebrates by firing off a space revolver – blasting holes in the walls of the station and deflating it like a punctured inner tube. Tom is left to patch holes and operate a bicycle pump to repair the station while at gunpoint, while Jerry comfortably reclines on the moon – which really is made of cheese – with a bulging belly and no worries of ever being hungry again. (Never mind the little matter of how is he breathing with no oxygen supply?)

The first of the three is more creative and original than what follows, and still allows the boys to cause some of their own mischief rather than leaving it all to the robots. It begins with an original idea – launching a ball-shaped supply satellite into space via a giant pinball-machine spring handle. The ball lands in space upon a space station shaped like a tipped roulette wheel, landing in a numbered loading dock on its surface to deposit its cargo – including fresh cheese, desired by Jerry. Jerry hops into his robot, while Tom (alerted by a rocket lit by a fuse ignited as the mouse-robot blasts through a doorway where the line is strung across) sends out the mechanical cat. As the cat closes in with jaws wide to swallow the mouse robot, Jerry shoots a blast of black smoke from the mouse-robot’s jets, leaving the cat-robot coughing and gasping for breath. (Do robots breathe?) The chase leads by Tom’s rolling recliner chair at the command console. The mouse robot scoots under Tom’s chair, while the cat-robot picks up the chair and Tom with him. Tom reaches for a remote and pushes a button to make the robot stop. However, his chair continues to roll – right into the wall. Tom returns to his robot, turns him around, and delivers a swift kick to the robot’s rear. Of course, kicking something of hard metal isn’t too conducive to good pedal health – and Tom’s toes find this out quickly enough, turning red and swelling like balloons, to the cat’s consternation. The remainder of the film does not deal with the robots, but ultimately has Tom fire Jerry off from the station via a space cannon, landing Jerry on the moon. Tom is so happy, he celebrates by firing off a space revolver – blasting holes in the walls of the station and deflating it like a punctured inner tube. Tom is left to patch holes and operate a bicycle pump to repair the station while at gunpoint, while Jerry comfortably reclines on the moon – which really is made of cheese – with a bulging belly and no worries of ever being hungry again. (Never mind the little matter of how is he breathing with no oxygen supply?)

The second film begins to become more robo-centric, with T&J themselves taking a much smaller share of the action. The robots’ chase uses a variant on a sequence first performed by T&J in “Mice Follies” for Hanna and Barbera, in which the pursuing cat-robot narrowly avoids both high and low obstacles during a chase by ducking under or stretching to rise above them – but nevertheless finally collides with a solid doorway at the end of the pursuit, leaving himself in an awkward mess. (This same shot is simply excised and reused verbatim toward the end of the third film in this trilogy.) The film also repeats the gag from Sylvester and Speedy’s “Nits and Volts” of having the robot pursuit run straight at the monitor camera – and right through Tom’s control panel. An additional sequence has the robot cat assume bipedal mode, armed with a space pistol. He knocks at Jerry’s mousehole, then produces the weapon. Jerry emerges in a miniature space tank, and raises a cannon to the barrel of the cat’s pistol – firing a shot at the cat right through the weapon. The cat’s lower engine platform falls out in a repeat of the “fallen pants” gag from “Robot Rabbit” and “Nuts and Volts”. The angered cat-robot takes out his frustrations on Tom, blasting his master with the same pistol. Tom turns the weapon on the robot and fires – but the robot’s metal only serves to plug up the end of the gun, reversing the force of the blast onto Tom once again, as the robot snickers with laughter. The film’s remaining sequences again abandon the robots, featuring a creative duel with an electro-magnet, in which Jerry repeatedly drops the mallet of a sledge-hammer onto Tom’s head and his ever-growing head-lump, and a downright weird ending where an explosive mixed by Jerry blasts the characters back in time to the Stone Age, where they begin the history of their never-ending chase as prehistoric Neanderthals.

The second film begins to become more robo-centric, with T&J themselves taking a much smaller share of the action. The robots’ chase uses a variant on a sequence first performed by T&J in “Mice Follies” for Hanna and Barbera, in which the pursuing cat-robot narrowly avoids both high and low obstacles during a chase by ducking under or stretching to rise above them – but nevertheless finally collides with a solid doorway at the end of the pursuit, leaving himself in an awkward mess. (This same shot is simply excised and reused verbatim toward the end of the third film in this trilogy.) The film also repeats the gag from Sylvester and Speedy’s “Nits and Volts” of having the robot pursuit run straight at the monitor camera – and right through Tom’s control panel. An additional sequence has the robot cat assume bipedal mode, armed with a space pistol. He knocks at Jerry’s mousehole, then produces the weapon. Jerry emerges in a miniature space tank, and raises a cannon to the barrel of the cat’s pistol – firing a shot at the cat right through the weapon. The cat’s lower engine platform falls out in a repeat of the “fallen pants” gag from “Robot Rabbit” and “Nuts and Volts”. The angered cat-robot takes out his frustrations on Tom, blasting his master with the same pistol. Tom turns the weapon on the robot and fires – but the robot’s metal only serves to plug up the end of the gun, reversing the force of the blast onto Tom once again, as the robot snickers with laughter. The film’s remaining sequences again abandon the robots, featuring a creative duel with an electro-magnet, in which Jerry repeatedly drops the mallet of a sledge-hammer onto Tom’s head and his ever-growing head-lump, and a downright weird ending where an explosive mixed by Jerry blasts the characters back in time to the Stone Age, where they begin the history of their never-ending chase as prehistoric Neanderthals.

Film #3, directed by Washam, is nearly a wash-out, as T&J themselves do virtually nothing but lounge in their easy chairs while the robots do the chasing. Tom stops briefly for lunch, getting frustrated when he is served a dose of oil instead of chow from a vending machine, intended for the metallic mining robots of the space station. Tom starts looking upon Jerry more as a tasty snack than a security risk. But even the mouse and cat robots get fed up with being the fall guys taking all the lumps. Each robot revolts against its master, placing a helmet upon their owner which allows the robots to electronically control them through their own remotes. T&J end the film by mindlessly exchanging repeated blows at their minions’ order – leaving things just about the way they should have been in the first place.

Film #3, directed by Washam, is nearly a wash-out, as T&J themselves do virtually nothing but lounge in their easy chairs while the robots do the chasing. Tom stops briefly for lunch, getting frustrated when he is served a dose of oil instead of chow from a vending machine, intended for the metallic mining robots of the space station. Tom starts looking upon Jerry more as a tasty snack than a security risk. But even the mouse and cat robots get fed up with being the fall guys taking all the lumps. Each robot revolts against its master, placing a helmet upon their owner which allows the robots to electronically control them through their own remotes. T&J end the film by mindlessly exchanging repeated blows at their minions’ order – leaving things just about the way they should have been in the first place.

“The Spy Swatter” (Warner, Daffy Duck/Speedy Gonzales 6/24/67 – Rudy Larriva, dir.) – receives brief mention. Speedy is selected by a mouse scientist as the only reliable messenger to deliver the formula for a super-energized ultra-high potency cheese that will give a mouse the strength of ten cats. As a demonstration, the scientist introduces Speedy to a robot cat named Hugo – the world’s strongest cat. Instructing Speedy to eat a sample of the cheese, the scientist sets the robot to kill mouse. Speedy is so shaken up, he nearly forgets to eat the cheese, but swallows it just as the robot gets him in the clutches of his paw. “Okay, you tin can cat, now you gonna get it”, challenges Speedy. A powerful sock sets the robot’s head into an an off-center tilt. A judo flip snaps the robot’s tail off, and leaves its remains piled in a crumpled heap. Speedy refers to the robot as “all broken up over the demonstration.” The cheese does not seem to be long-lasting in effect, as Speedy does not use any super-strength for the rest of the cartoon, but relies sonly on his traditional speed in making delivery of the formula to a cheese factory. The nonsensical plot casts Sam (the orange tabby with Frank Fontaine voice who often was a rival to Sylvester) as the head of a secret agency of cats, who hires Daffy Duck (for lack of ability to economically animate Sylvester) as a spy/secret agent to intercept and obtain the secret formula. Fortunately for me, there are no further robots involved in these exploits – so the less said, the better.

“The Spy Swatter” (Warner, Daffy Duck/Speedy Gonzales 6/24/67 – Rudy Larriva, dir.) – receives brief mention. Speedy is selected by a mouse scientist as the only reliable messenger to deliver the formula for a super-energized ultra-high potency cheese that will give a mouse the strength of ten cats. As a demonstration, the scientist introduces Speedy to a robot cat named Hugo – the world’s strongest cat. Instructing Speedy to eat a sample of the cheese, the scientist sets the robot to kill mouse. Speedy is so shaken up, he nearly forgets to eat the cheese, but swallows it just as the robot gets him in the clutches of his paw. “Okay, you tin can cat, now you gonna get it”, challenges Speedy. A powerful sock sets the robot’s head into an an off-center tilt. A judo flip snaps the robot’s tail off, and leaves its remains piled in a crumpled heap. Speedy refers to the robot as “all broken up over the demonstration.” The cheese does not seem to be long-lasting in effect, as Speedy does not use any super-strength for the rest of the cartoon, but relies sonly on his traditional speed in making delivery of the formula to a cheese factory. The nonsensical plot casts Sam (the orange tabby with Frank Fontaine voice who often was a rival to Sylvester) as the head of a secret agency of cats, who hires Daffy Duck (for lack of ability to economically animate Sylvester) as a spy/secret agent to intercept and obtain the secret formula. Fortunately for me, there are no further robots involved in these exploits – so the less said, the better.

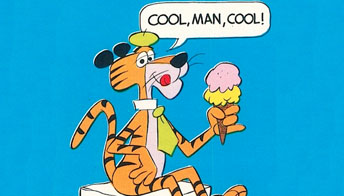

“Cool Cat” – (Warner, Cool Cat, 10/14/67 – Alex Lovy, dir.). This was the episode that introduced Warners’ new line of late ‘60’s short-lived series characters, to be followed by Merlin the Magic Mouse, and a few seasons later, Bunny and Claude. While their screen presence may not have been the most memorable, they continued to have life as comic book franchises considerably after the demise of the theatrical cartoon. In fact, I knew of the characters as extra features in Gold Key comics decades before I ever got to see any of them on film. Perhaps Cool Cat’s most delayed legacy was to become the subject of a running gag in “The Sylvester and Tweety Mysteries”, a series known for finding cameo roles for various and sundry Looney Tunes characters of the golden age. Someone in the writer’s pool must have quipped a challenge about finding any convincing excuse for including a cameo for Cool Cat. The writers took up this dare – so, while I am not sure if the tiger ever appeared in the flesh during the run of the show, it seemed that every (or nearly every) episode featured some likeness of the cat in paintings, statuary, poster art, or anywhere they could pencil him into a background – often accompanied by a few bars of his twangy theme song. He was the Warners’ equivalent of the Pizza Planet truck making mysterious appearances in every Pixar production for good luck.

“Cool Cat” – (Warner, Cool Cat, 10/14/67 – Alex Lovy, dir.). This was the episode that introduced Warners’ new line of late ‘60’s short-lived series characters, to be followed by Merlin the Magic Mouse, and a few seasons later, Bunny and Claude. While their screen presence may not have been the most memorable, they continued to have life as comic book franchises considerably after the demise of the theatrical cartoon. In fact, I knew of the characters as extra features in Gold Key comics decades before I ever got to see any of them on film. Perhaps Cool Cat’s most delayed legacy was to become the subject of a running gag in “The Sylvester and Tweety Mysteries”, a series known for finding cameo roles for various and sundry Looney Tunes characters of the golden age. Someone in the writer’s pool must have quipped a challenge about finding any convincing excuse for including a cameo for Cool Cat. The writers took up this dare – so, while I am not sure if the tiger ever appeared in the flesh during the run of the show, it seemed that every (or nearly every) episode featured some likeness of the cat in paintings, statuary, poster art, or anywhere they could pencil him into a background – often accompanied by a few bars of his twangy theme song. He was the Warners’ equivalent of the Pizza Planet truck making mysterious appearances in every Pixar production for good luck.

Colonel Rimfire is a modern-day big game hunter – who can’t seem to find any big game. Rather than rely on old-fashioned safari transportation aboard a live elephant, Rimfire prefers a new-fangled motorized job made of metal, offering several advantages over a real elephant. Its gasoline-powered engine guarantees speed in stalking on its wheeled feet. Rather than be exposed to view, Rimfire is able to ride concealed inside the elephant’s torso by means of entry through a hatch in the robot’s back. The mechanical trunk serves multiple purposes, bending to form a viewing periscope for the rider inside, and serving as a holder to steady the barrel of a hunter’s rifle, sticking out the end of the trunk tip to fire like a cannon. It seems that Rimfire has a sure-fire advantage which should help his hunt tremendously – but he has not reckoned on a certain Cool Cat, a hipster tiger, who saunters along through the jungle carrying a small shade umbrella above his head. “I taught I taw a putty tat – a tiger-type putty tat!”, says Rimfire, determined to prove that he’s really a Warner Brothers’ character. As Cool Cat bends to sniff a flower, Rimfire takes a shot at him with his trunk-gun, shattering the tiger’s umbrella. Cool Cat looks around, but all he sees is the elephant – convincing enough that the Cat thinks he’s real. “Quick. Let’s split the scene. Somebody’s shooting at us”, says Cool to the elephant. Cool runs, but Rimfire does not follow. Not realizing it his his own shot that the tiger is talking about, Rimfire assumes someone else must be shooting, and looks around for a place to hide. He chooses to jump his elephant through a hedgerow – and plummets into a coyote-worthy canyon on the other side of the hedge.

Colonel Rimfire is a modern-day big game hunter – who can’t seem to find any big game. Rather than rely on old-fashioned safari transportation aboard a live elephant, Rimfire prefers a new-fangled motorized job made of metal, offering several advantages over a real elephant. Its gasoline-powered engine guarantees speed in stalking on its wheeled feet. Rather than be exposed to view, Rimfire is able to ride concealed inside the elephant’s torso by means of entry through a hatch in the robot’s back. The mechanical trunk serves multiple purposes, bending to form a viewing periscope for the rider inside, and serving as a holder to steady the barrel of a hunter’s rifle, sticking out the end of the trunk tip to fire like a cannon. It seems that Rimfire has a sure-fire advantage which should help his hunt tremendously – but he has not reckoned on a certain Cool Cat, a hipster tiger, who saunters along through the jungle carrying a small shade umbrella above his head. “I taught I taw a putty tat – a tiger-type putty tat!”, says Rimfire, determined to prove that he’s really a Warner Brothers’ character. As Cool Cat bends to sniff a flower, Rimfire takes a shot at him with his trunk-gun, shattering the tiger’s umbrella. Cool Cat looks around, but all he sees is the elephant – convincing enough that the Cat thinks he’s real. “Quick. Let’s split the scene. Somebody’s shooting at us”, says Cool to the elephant. Cool runs, but Rimfire does not follow. Not realizing it his his own shot that the tiger is talking about, Rimfire assumes someone else must be shooting, and looks around for a place to hide. He chooses to jump his elephant through a hedgerow – and plummets into a coyote-worthy canyon on the other side of the hedge.

Rimfire slowly pushes his mechanical elephant up the slope of the canyon wall, cursing himself for being so stupid as to fall for Cool’s warning. At the top of the canyon ledge stands Cool, seeing only the elephant coming up from the canyon. He reaches out to give his new pal a hand, grabbing hold of the elephant’s trunk. This places Rimfire, still pushing from behind, off balance – and the unlucky blighter of a hunter falls once again into the canyon. Cool catches his first glimpse of Rimfire, and informs the elephant that he had a hunter tailing him. He again tries to lead the elephant to safe ground, but the beast does not follow. “Not very bright, are you”, says Cool to his mute friend, and again grabs hold of the trunk, taking the beast under his wing, in hopes of showing him the ropes about making a life in the jungle. “My four-wheel drive elephant is gone”, observes Rimfire, climbing back over the canyon ledge. “Nobody steals my pachydermy. This means war!” Rimfire pursues, but encounters a real elephant who emerges from the brush, smitten with the passing robot. Rimfire mistakes the real beast for his mechanical steed, but can’t understand why the trap door won’t open in its back. For his troubles, Rimfire gets firmly planted into the ground by a beating from the real elephant’s trunk. Cool passes again, trying to teach the robot elephant to forage for food. Rimfire provides a choice morsel – an “exploding pineapple” in the form of a hand-grenade. He attempts to pull the grenade’s pin – but instead, his dentures fall out when he tugs on the pin, and he tosses the grenade with an attached chattering set of false teeth at Cool, the pin still firmly in the grenade. Cool thinks it’s a new kind of tropical fruit, but when the elephant shows no interest in it, Cool agrees, “I don’t blame you”, and tosses it away. When the grenade returns, Rimfire thinks the chattering teeth are a tarantula, and takes a shot at them. His shot loosens the firing pin of the grenade, and he and the dentures get blasted. A frazzled Rimfire is left to reassemble his dental work like a jigsaw puzzle, bicuspid by bicuspid, molar by molar.

Rimfire slowly pushes his mechanical elephant up the slope of the canyon wall, cursing himself for being so stupid as to fall for Cool’s warning. At the top of the canyon ledge stands Cool, seeing only the elephant coming up from the canyon. He reaches out to give his new pal a hand, grabbing hold of the elephant’s trunk. This places Rimfire, still pushing from behind, off balance – and the unlucky blighter of a hunter falls once again into the canyon. Cool catches his first glimpse of Rimfire, and informs the elephant that he had a hunter tailing him. He again tries to lead the elephant to safe ground, but the beast does not follow. “Not very bright, are you”, says Cool to his mute friend, and again grabs hold of the trunk, taking the beast under his wing, in hopes of showing him the ropes about making a life in the jungle. “My four-wheel drive elephant is gone”, observes Rimfire, climbing back over the canyon ledge. “Nobody steals my pachydermy. This means war!” Rimfire pursues, but encounters a real elephant who emerges from the brush, smitten with the passing robot. Rimfire mistakes the real beast for his mechanical steed, but can’t understand why the trap door won’t open in its back. For his troubles, Rimfire gets firmly planted into the ground by a beating from the real elephant’s trunk. Cool passes again, trying to teach the robot elephant to forage for food. Rimfire provides a choice morsel – an “exploding pineapple” in the form of a hand-grenade. He attempts to pull the grenade’s pin – but instead, his dentures fall out when he tugs on the pin, and he tosses the grenade with an attached chattering set of false teeth at Cool, the pin still firmly in the grenade. Cool thinks it’s a new kind of tropical fruit, but when the elephant shows no interest in it, Cool agrees, “I don’t blame you”, and tosses it away. When the grenade returns, Rimfire thinks the chattering teeth are a tarantula, and takes a shot at them. His shot loosens the firing pin of the grenade, and he and the dentures get blasted. A frazzled Rimfire is left to reassemble his dental work like a jigsaw puzzle, bicuspid by bicuspid, molar by molar.

Cool is still looking for food, when Rimfire spots a native tom tom drum. He hides inside it to ambush the tiger. Cool also spots the drum, and remarks, “A jungle telephone. We’ll send out for something to eat.” Grabbing two large drumsticks, he beats out a rhythm on the drum, then departs with the elephant. Rimfire emerges through the drum’s canvas top, his ears ringing with the sound of a telephone busy-signal. Cool’s next lesson to the elephant is self-defense. Cool exhibits a little “jungle judo” in the form of karate chops on a large bush – not realizing he is beating up on Rimfire within it. Then he gives the elephant a push toward the bush for his turn. The robot elephant free-wheels toward Rimfire. “Mad elephant”, shouts Rimfire, abandoning his hiding place to run. He is picked up on the face of the robot, then the two of them crash into the side of a cliff. “No no, you weren’t paying attention. Let’s try that again”, says Cool, tugging the elephant back by the tail. Rimfire, fattened into the face of the cliff, pops out to say, “Again? I quit!” Stating goodbye forever, Rimfire races past Cool to regain his elephant, and put-puts past Cool to return to civilization – until the motor dies. Rimfire emerges from the driver’s seat with a gasoline can, and asks Cool how far it is to the nearest filling station. Cool points him down a road – only 2,000 miles. As the film ends, Cool finally gets a better look at the elephant, opening a hatch in its rear to reveal its oversized engine works. “They’re not making elephants like they used to anymore”, he observes to the audience, for the fade out.

Cool is still looking for food, when Rimfire spots a native tom tom drum. He hides inside it to ambush the tiger. Cool also spots the drum, and remarks, “A jungle telephone. We’ll send out for something to eat.” Grabbing two large drumsticks, he beats out a rhythm on the drum, then departs with the elephant. Rimfire emerges through the drum’s canvas top, his ears ringing with the sound of a telephone busy-signal. Cool’s next lesson to the elephant is self-defense. Cool exhibits a little “jungle judo” in the form of karate chops on a large bush – not realizing he is beating up on Rimfire within it. Then he gives the elephant a push toward the bush for his turn. The robot elephant free-wheels toward Rimfire. “Mad elephant”, shouts Rimfire, abandoning his hiding place to run. He is picked up on the face of the robot, then the two of them crash into the side of a cliff. “No no, you weren’t paying attention. Let’s try that again”, says Cool, tugging the elephant back by the tail. Rimfire, fattened into the face of the cliff, pops out to say, “Again? I quit!” Stating goodbye forever, Rimfire races past Cool to regain his elephant, and put-puts past Cool to return to civilization – until the motor dies. Rimfire emerges from the driver’s seat with a gasoline can, and asks Cool how far it is to the nearest filling station. Cool points him down a road – only 2,000 miles. As the film ends, Cool finally gets a better look at the elephant, opening a hatch in its rear to reveal its oversized engine works. “They’re not making elephants like they used to anymore”, he observes to the audience, for the fade out.

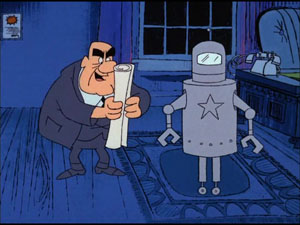

“Les Miserobots” (DePatie-Freleng/United Artists, The Inspector, 3/21/68 – Gerry Chiniquy, dir.) – A clever, well-timed installment. The inspector has been “busy” for several months trying to catch a criminal known as Louie De Louse, making no progress. He narrates that he was busy examining clues (actually reading “Le Funny Comics”), when he is called to the commissioner’s office. The commissioner presents his latest acquisition in the name of crime prevention – an automated policeman. It is a metallic grey robot with a star painted on its cylindrical chest, and a domed metal head with a glass pane that serves as its eyes, topped with a beeping antenna. A flip of a switch, and a feed in of information (by merely showing the robot Louie’s wanted poster), and the robot gives a readout in its eye panel of three slot-maching wheels, all with pictures of Louie. The robot exits the office, and in five seconds returns with the criminal in hand – er, claw. “Why that’s incredible! Just think of all the criminals you can get rid of”, states the Inspector. “That’s not all I can get rid of”, remarks the commissioner, with a telling smile toward the Inspector. The image of the Inspector transforms to a black and white photo on the front page of a newspaper, with headline, “Policeman loses job to robot.” The Inspector himself is reading the paper from a park bench, down and out. He crumples up the paper in anger and tosses it on the ground. Immediately, the robot responds to the scene, depositing both the paper and the Inspector in a nearby wastebasket to keep the park free of litter. The Inspector rises from the trash, his narration stating “There was only one way to get my job back”, as the irises of his eyes transform into the word, “Kill”,

“Les Miserobots” (DePatie-Freleng/United Artists, The Inspector, 3/21/68 – Gerry Chiniquy, dir.) – A clever, well-timed installment. The inspector has been “busy” for several months trying to catch a criminal known as Louie De Louse, making no progress. He narrates that he was busy examining clues (actually reading “Le Funny Comics”), when he is called to the commissioner’s office. The commissioner presents his latest acquisition in the name of crime prevention – an automated policeman. It is a metallic grey robot with a star painted on its cylindrical chest, and a domed metal head with a glass pane that serves as its eyes, topped with a beeping antenna. A flip of a switch, and a feed in of information (by merely showing the robot Louie’s wanted poster), and the robot gives a readout in its eye panel of three slot-maching wheels, all with pictures of Louie. The robot exits the office, and in five seconds returns with the criminal in hand – er, claw. “Why that’s incredible! Just think of all the criminals you can get rid of”, states the Inspector. “That’s not all I can get rid of”, remarks the commissioner, with a telling smile toward the Inspector. The image of the Inspector transforms to a black and white photo on the front page of a newspaper, with headline, “Policeman loses job to robot.” The Inspector himself is reading the paper from a park bench, down and out. He crumples up the paper in anger and tosses it on the ground. Immediately, the robot responds to the scene, depositing both the paper and the Inspector in a nearby wastebasket to keep the park free of litter. The Inspector rises from the trash, his narration stating “There was only one way to get my job back”, as the irises of his eyes transform into the word, “Kill”,

As the robot patrols, pausing at a busy intersection for the “Don’t Walk” sign, the Inspector attempts to push the robot from behind into oncoming traffic. However, the robot won’t budge. Two mechanical hands emerge from a hatch in the robot’s back, one suspending the Inspector in the air by his coat, and the other socking him in the belly with a boxing glove. The crosswalk sign changes to “Walk” as the robot drops the Inspector and proceeds, The angered Inspector pursues into the street, just as the signal returns to “Don’t Walk”. The Inspector is mowed down by the traffic – and the robot returns to issue him a jaywalking ticket. The Inspector rises to pull his revolver on the robot, but is mowed down by another wave of traffic, so that when he fires, the bullet barely exits the barrel, and simply plops down upon the ground. The robot is next seen conducting traffic at another location in the middle of a street. The Inspector rises from under a manhole cover, placing a lit stick of TNT behind the robot, then ducks back in the manhole for safety. The rear hatch of the robot opens again, as one of its mechanical hands picks up the dynamite stick, turns it sideways, and drops it through one of the vent holes of the manhole cover. “Oh, no”, groans the voice of the Inspector below. The cover rises, the Inspector on the verge of emerging to escape, when the explosive blast frazzles him in his tracks. The singed Inspector merely shifts into reverse, and disappears back into the hole, replacing the cover above him.

As the robot patrols, pausing at a busy intersection for the “Don’t Walk” sign, the Inspector attempts to push the robot from behind into oncoming traffic. However, the robot won’t budge. Two mechanical hands emerge from a hatch in the robot’s back, one suspending the Inspector in the air by his coat, and the other socking him in the belly with a boxing glove. The crosswalk sign changes to “Walk” as the robot drops the Inspector and proceeds, The angered Inspector pursues into the street, just as the signal returns to “Don’t Walk”. The Inspector is mowed down by the traffic – and the robot returns to issue him a jaywalking ticket. The Inspector rises to pull his revolver on the robot, but is mowed down by another wave of traffic, so that when he fires, the bullet barely exits the barrel, and simply plops down upon the ground. The robot is next seen conducting traffic at another location in the middle of a street. The Inspector rises from under a manhole cover, placing a lit stick of TNT behind the robot, then ducks back in the manhole for safety. The rear hatch of the robot opens again, as one of its mechanical hands picks up the dynamite stick, turns it sideways, and drops it through one of the vent holes of the manhole cover. “Oh, no”, groans the voice of the Inspector below. The cover rises, the Inspector on the verge of emerging to escape, when the explosive blast frazzles him in his tracks. The singed Inspector merely shifts into reverse, and disappears back into the hole, replacing the cover above him.

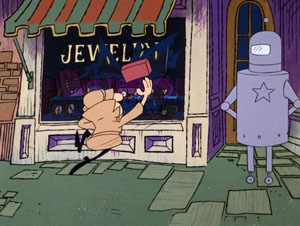

Resorting to heavy artillery, the Inspector purchases a war surplus bazooka, which he places in wait around a corner next to a tree. Rounding the corner, the Inspector attracts the robot’s attention, by deliberately tossing a brick through a jewelry store window. The robot pirsues him back to the corner, where the Inspector levels the bazooka at him and fires. The shell merely bounces harmlessly off the robot’s chest, while the blast from the bazooka’s rear fells the tree behind the Inspector, right on top of him. Next, as the robot guards a financial establishment known as “Le Left Bank”, the Inspector attempts to creep up behind him with a tank of gas and a welding torch. Unfortunately, he can’t get the torch’s starter flame to light, and the robot offers a cigarette lighter to get things started, while the gas continues to leak from the Inspector’s tank. BOOM! The blackened Inspector returns the lighter, wearily uttering, “Thanks a lot”, then collapses. The robot is next seen patrolling in front of Surete headquarters, as the camera pans to the roof. Above, the Inspector has installed two new apparatus upon the building – a crane, carrying a giant magnet – plus a large cannon. The Inspector peers over the ledge, aiming the magnet at the robot below, then steps back a few paces to operate a crank to lower the crane’s line to the ground. While he is cranking, the robot leaves, and the commissioner’s squad car pulls up in its place. The Inspector hears the magnet hit metal, and reels in, simultaneously lighting the fuse in the cannon. “He’ll never know what hit him”, he gloats. “Inspector, what are you do-ingggggg”, rings out the voice of the commissioner, his car caught on the magnet, as the startled Inspector lets go of the crane crank, allowing the commissioner to plunge to the ground. To make matters worse, the cannon fires, its cannonball catching the Inspector, and sailing him across Paris, where he collides with a clang into the Eiffel Tower.

Resorting to heavy artillery, the Inspector purchases a war surplus bazooka, which he places in wait around a corner next to a tree. Rounding the corner, the Inspector attracts the robot’s attention, by deliberately tossing a brick through a jewelry store window. The robot pirsues him back to the corner, where the Inspector levels the bazooka at him and fires. The shell merely bounces harmlessly off the robot’s chest, while the blast from the bazooka’s rear fells the tree behind the Inspector, right on top of him. Next, as the robot guards a financial establishment known as “Le Left Bank”, the Inspector attempts to creep up behind him with a tank of gas and a welding torch. Unfortunately, he can’t get the torch’s starter flame to light, and the robot offers a cigarette lighter to get things started, while the gas continues to leak from the Inspector’s tank. BOOM! The blackened Inspector returns the lighter, wearily uttering, “Thanks a lot”, then collapses. The robot is next seen patrolling in front of Surete headquarters, as the camera pans to the roof. Above, the Inspector has installed two new apparatus upon the building – a crane, carrying a giant magnet – plus a large cannon. The Inspector peers over the ledge, aiming the magnet at the robot below, then steps back a few paces to operate a crank to lower the crane’s line to the ground. While he is cranking, the robot leaves, and the commissioner’s squad car pulls up in its place. The Inspector hears the magnet hit metal, and reels in, simultaneously lighting the fuse in the cannon. “He’ll never know what hit him”, he gloats. “Inspector, what are you do-ingggggg”, rings out the voice of the commissioner, his car caught on the magnet, as the startled Inspector lets go of the crane crank, allowing the commissioner to plunge to the ground. To make matters worse, the cannon fires, its cannonball catching the Inspector, and sailing him across Paris, where he collides with a clang into the Eiffel Tower.

A new news headline reads, “Robot Cleans Up Crime In Paris”. The commissioner receives a call from whoever is his own higher-up, who informs the commissioner that he is pleased with the performance of the robot. However, there is more. “You’re promoting the robot to whose job?” The scene abruptly wipes to a skid row soup kitchen. The Inspector, his trench coat battered and torn, is handed a bowl, and complains, “How do they expect you to eat this slop?” A familiar voice is heard beside him, as the next derelict at the table turns out to be none other than the out-of-uniform commissioner – also out of work – who barks, “Aw, shut up, and pass the salt!”

A new news headline reads, “Robot Cleans Up Crime In Paris”. The commissioner receives a call from whoever is his own higher-up, who informs the commissioner that he is pleased with the performance of the robot. However, there is more. “You’re promoting the robot to whose job?” The scene abruptly wipes to a skid row soup kitchen. The Inspector, his trench coat battered and torn, is handed a bowl, and complains, “How do they expect you to eat this slop?” A familiar voice is heard beside him, as the next derelict at the table turns out to be none other than the out-of-uniform commissioner – also out of work – who barks, “Aw, shut up, and pass the salt!”

“Technology, Phooey” (DePatie/Freleng/United Artists, The Ant and the Aardvark, 6/25/69 – Gerry Chiniquy, dir.), is essentially a reworking of Chuck Jones’ “To Hare Is Human” centering on the idea of obtaining a computer super-brain to do your thinking for you. Aardvark, constantly frustrated in his efforts to catch an ant, purchases a Wizard do-it-yourself electro-kit, and constructs what appears to be a super-computer with a large television monitor on which words appear to accompany its speech from a voice-synthesizer (a voice that sounds roughly like an impersonation of Paul Lynde). The screen directs Aardvark to an anthill one mile straight ahead – “You can’t miss it”. Aardvark sticks his nose into the hill to turn on his trademark vacuum suction – but inhales burning wood from the ant’s miniature fireplace. Turning red hot, Aardvark has to dive in the lake to put out the fire. “Hi again”, responds the monitor as Aardvark returns to the machine. “How did it go? Not so hot, huh?”, the machine continues. “On the contrary, I got a hot foot, heartburn, and hot flashes all at once, but no ant”, responds Aardvark. The machine next suggests a can of insecticide. Aardvark tries it, but gets the aerosol nozzle pointed in the wrong direction when he presses the can’s button, taking the hit himself of the toxic fumes. Aardvark turns all manner of colors, including rainbow and polka dot, and collapses. Ant remarks, “He must be having a bad trip.” The machine’s third suggestion is some quicksand. Aardvark pours some outside of Ant’s anthill, and baits it with a cherry on top. The Ant attempts to obtain the cherry, and sinks into the puddle. Aardvark sticks his nose in the puddle to suck up the Ant – but the quicksand is so effective, Aardvark is sucked into the puddle too. Ant somehow comes up from underground in the entrance of his anthill, eating the cherry. Aardvark is still stuck in the puddle, with only the tip of his nose above ground through which to breathe. Ant disposes of the cherry pit by tossing it into Aardvark’s nose as if it were a wastebasket. Aardvark swallows the pit, then says through his talking nose – “I could say something right now, but it would only be censored.” Aardvark finally returns to his invention, and confronts it. “As a computer, you stink”, he shouts. “Who said I was a computer?”, responds the machine. “I’m an automatic pop-up toaster, and I’ll prove it.” A flood of toasted bread slices suddenly pops out of the control panel of the device, covering Aardvark. “Anybody got a pound of butter?”, Aardvark asks the audience, for the fade out.